Vague specs produce vague code. When working with AI coding agents, the quality of your specifications directly determines the quality of the output. This post covers how to write specs that leave no room for interpretation.

If you’re new to spec-driven development, start with the introduction for context on what it is and which tools exist.

The problem with prose#

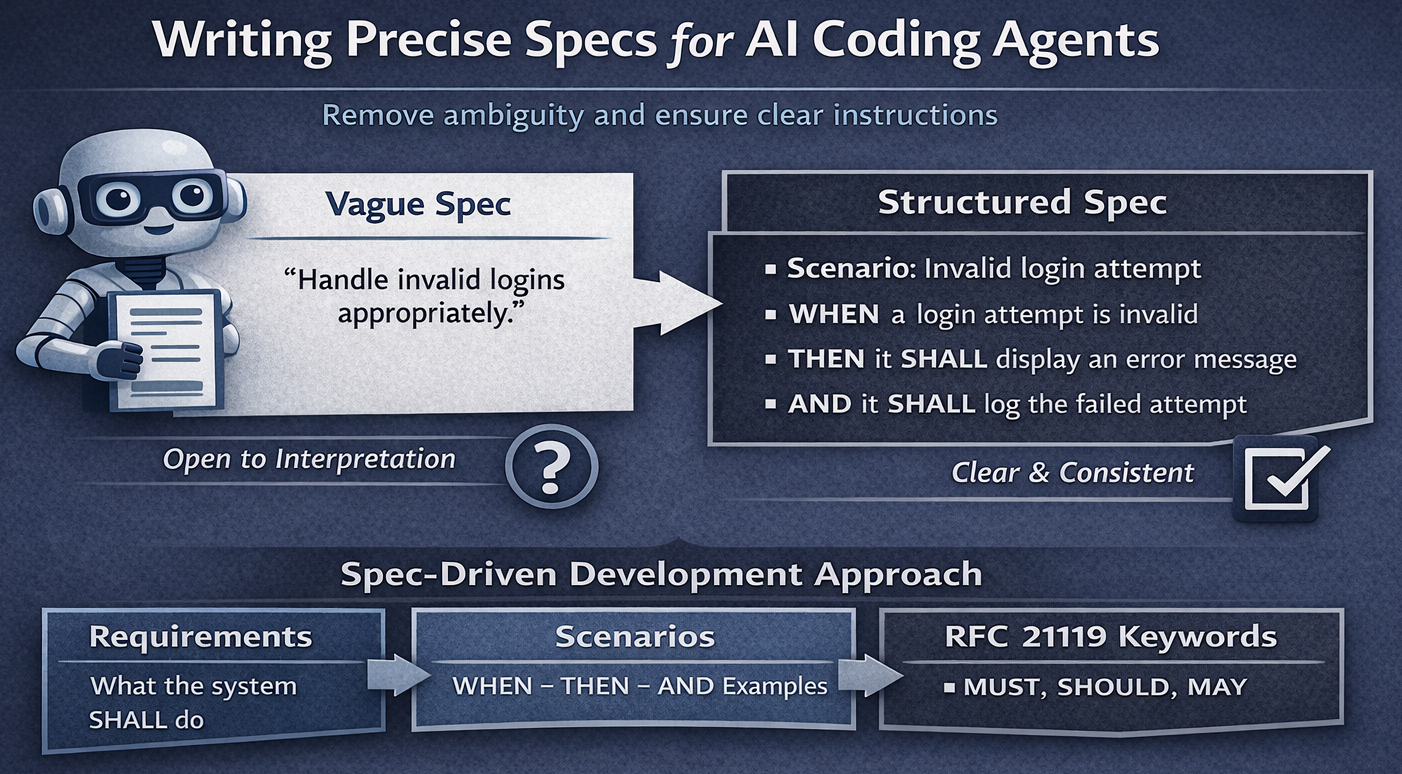

Vibe coding works like this: you describe what you want in conversational prose, the AI generates code, you iterate until it looks right. The problem is that natural language is ambiguous. “The system should handle invalid login attempts appropriately” means different things to different people. The AI will interpret it however its training suggests, which may not match your intent.

Spec-driven development solves the drift problem by making specifications the primary artifact.

But it raises a new question: how do you structure specs for both clarity and effectiveness?

By borrowing patterns from Behavior-Driven Development (BDD) and the RFC 2119 requirement keywords, you can write specs that are both human-readable and machine-parseable.

A structure borrowed from BDD#

BDD is a software development practice that emerged from Test-Driven Development. Where TDD focuses on testing implementation, BDD focuses on specifying behavior from the user’s perspective. Teams write specifications in natural language that both stakeholders and developers can understand, then automate those specifications as tests.

Gherkin is the structured language BDD uses. It provides keywords like Feature, Scenario, Given, When, Then, and And that make specifications both readable and executable. Tools like Cucumber parse Gherkin files and run them as automated tests.

The core pattern is Given-When-Then:

Given some initial context

When an action occurs

Then expect this outcomeFor spec-driven development with AI agents, we adapt this to Markdown using Requirements, Scenarios, and WHEN-THEN-AND blocks. This preserves the clarity of Gherkin while staying in a format that works everywhere.

The anatomy of a spec file#

Create one spec file per feature. Each spec file contains:

- Purpose: A summary of the feature and why it matters

- Requirements: High-level capabilities the feature must have

- Scenarios: Specific behaviors under each requirement

Here’s the structure:

# Feature Name Specification

## Purpose

One paragraph describing what this spec covers and why it matters.

## Requirements

### Requirement: Capability Name

Brief description of the requirement.

#### Scenario: Specific behavior

- **WHEN** a specific condition occurs

- **THEN** it SHALL do something specific

- **AND** it SHALL also do this other thingRFC 2119 keywords#

RFC 2119 defines requirement keywords used in Internet standards. These keywords eliminate ambiguity about whether something is mandatory, recommended, or optional:

| Keyword | Alternative | Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| SHALL | MUST | Absolute requirement |

| SHALL NOT | MUST NOT | Absolute prohibition |

| SHOULD | RECOMMENDED | Strong recommendation, but valid exceptions may exist |

| SHOULD NOT | NOT RECOMMENDED | Strong discouragement, but valid exceptions may exist |

| MAY | OPTIONAL | Truly optional |

I found that using the full set matters. Popular SDD frameworks like OpenSpec default to SHALL only. This works for core requirements, but real systems have nuance:

- Performance optimizations that are nice to have but not critical

- Security hardening that depends on deployment context

- Convenience features that some users want and others don’t

Using only SHALL forces you to either make everything mandatory or omit optional behaviors entirely. The full RFC 2119 vocabulary lets you express degrees of importance.

Real examples#

Example: Database driver authentication#

This example is adapted from exarrow-rs, an ADBC driver for Exasol databases.

### Requirement: Authentication

The system SHALL implement Exasol's authentication mechanisms securely.

#### Scenario: Username and password authentication

- **WHEN** authenticating with username and password

- **THEN** it SHALL send credentials securely over the connection

- **AND** it SHALL support encrypted password transmission

#### Scenario: Authentication failure

- **WHEN** authentication fails

- **THEN** it SHALL return an error with the failure reason

- **AND** it SHALL close the connection

- **AND** it SHALL NOT retry automatically to avoid account lockoutNotice the SHALL NOT in the last scenario. This explicitly prohibits automatic retry, which prevents the agent from adding “helpful” retry logic that could lock out users.

Example: Calculator expression evaluation#

This example is adapted from crabculator, a terminal-based calculator.

### Requirement: Expression Evaluation

The system SHALL evaluate mathematical expressions and return results.

#### Scenario: Evaluate arithmetic expression

- **WHEN** a valid arithmetic expression is evaluated (e.g., `5 + 3 * 2`)

- **THEN** it SHALL return the computed numeric result (e.g., `11`)

#### Scenario: Evaluate expression with parentheses

- **WHEN** an expression with parentheses is evaluated (e.g., `(5 + 3) * 2`)

- **THEN** it SHALL respect operator precedence and grouping (e.g., `16`)

#### Scenario: Evaluate invalid expression

- **WHEN** an invalid expression is evaluated (e.g., `5 + + 3`, `5 / 0`)

- **THEN** it SHALL return an error with a descriptive message

- **AND** it SHOULD indicate the position of the error in the expression

- **AND** it MAY suggest corrections for common mistakesThis scenario mixes all three requirement levels:

- Returning results and errors is mandatory (SHALL)

- Indicating error position is recommended (SHOULD)

- Suggesting corrections is optional (MAY)

Writing effective scenarios#

Be specific about triggers#

Bad:

- **WHEN** there's an error

- **THEN** it SHALL handle it appropriatelyGood:

- **WHEN** the database returns error code 42000 (syntax error)

- **THEN** it SHALL wrap it in a QuerySyntaxError

- **AND** it SHALL include the original SQL in the error message

- **AND** it SHALL NOT include credentials in error outputCover edge cases explicitly#

If you don’t specify behavior for edge cases, the agent will guess:

#### Scenario: Empty result set

- **WHEN** a SELECT query returns zero rows

- **THEN** it SHALL return an empty RecordBatch

- **AND** it SHALL include the schema in the empty batch

- **AND** it SHALL NOT return null or throw an exception

#### Scenario: Null values in results

- **WHEN** result data contains NULL values

- **THEN** it SHALL preserve nulls in the Arrow representation

- **AND** it SHALL NOT substitute default values for nullsState what should NOT happen#

Prohibitions are as important as requirements:

#### Scenario: Error logging

- **WHEN** logging connection errors

- **THEN** it SHALL log the error type and message

- **AND** it SHALL NOT log passwords

- **AND** it SHALL NOT log full connection strings

- **AND** it SHALL NOT expose stack traces in production modePutting it together#

Effective specs for AI coding agents:

- Use structured format: Requirements → Scenarios → WHEN-THEN-AND

- Apply RFC 2119 keywords: SHALL, SHOULD, MAY (and their negatives)

- Be specific: Name error codes, specify thresholds, define exact behaviors

- Cover edge cases: Empty results, null values, timeouts, failures

- State prohibitions: What the system SHALL NOT do is as important as what it SHALL do

- Keep specs alive: Specs should evolve with the code, not be discarded after implementation

The investment in writing precise specs pays off in reduced back-and-forth, fewer misinterpretations, and code that actually matches your intent.